Hooded Oriole

General Description

The adult male is mainly orange but with a black back, tail, face, and bib. The dark wing shows two white wingbars, the upper one stronger. The female is plain olive-green above and yellowish-green below, and is easily confused with the female Orchard Oriole. Hooded is somewhat larger than Orchard overall with a longer bill and a longer tail. See field guides for identification pointers for separating the various oriole species in immature and female plumages.

The Hooded Oriole breeds from California across the lower Southwest to southern Texas and adjacent parts of northern Mexico, and down both coasts of Mexico. Northern populations move south to Mexico for the winter. Most records from the Pacific Northwest are spring “overshoots” of returning migrants, with a few extending into July. Idaho’s only record, in 2000, stayed right through June and July. Roughly one-third of Oregon’s twenty-plus records have occurred in winter, including several birds that stayed for many weeks. British Columbia has about six records, most in spring and all from coastal sites; one bird remained near Prince Rupert for the entire winter (19 November–2 April). Washington’s seven accepted records are all from the Westside lowlands; six were from spring and the other was in July.

Revised November 2007

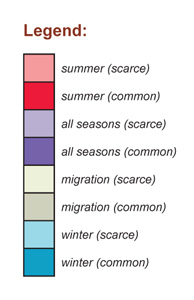

North American Range Map

Family Members

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus

BobolinkDolichonyx oryzivorus Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus

Red-winged BlackbirdAgelaius phoeniceus Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor

Tricolored BlackbirdAgelaius tricolor Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta

Western MeadowlarkSturnella neglecta Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus

Yellow-headed BlackbirdXanthocephalus xanthocephalus Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus

Rusty BlackbirdEuphagus carolinus Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus

Brewer's BlackbirdEuphagus cyanocephalus Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula

Common GrackleQuiscalus quiscula Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus

Great-tailed GrackleQuiscalus mexicanus Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater

Brown-headed CowbirdMolothrus ater Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius

Orchard OrioleIcterus spurius Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus

Hooded OrioleIcterus cucullatus Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii

Bullock's OrioleIcterus bullockii Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula

Baltimore OrioleIcterus galbula Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum

Scott's OrioleIcterus parisorum