Arctic Tern

The Washington representatives of this family can be split into two groups, or subfamilies. The adaptable gulls are the most familiar. Sociable in all seasons, they are mainly coastal, but a number of species also nest inland. Many—but not all—are found around people. Gulls have highly variable foraging techniques and diets. Terns forage in flight, swooping to catch fish or insects. They dive headfirst into the water for fish. Although they are likely to be near water, they spend less time swimming than gulls.

General Description

The Arctic Tern is slightly smaller than the Common Tern with long, narrow wings and very short legs. In breeding plumage, the Arctic Tern has a light gray mantle and belly. The lower half of the face is white, and the upper sports a black cap without a crest. The tail is white, and usually projects beyond the wingtips when the bird is perched. The bill and legs are red. The adult does not show the black 'wedge' in the outer flight feathers that is present on Common Terns, and instead shows a thin, black border on the trailing edge of the primaries, visible from below. In the non-breeding season, the Arctic Tern has a receding black cap, with a white forehead extending halfway back its head, and the legs and beak are black. Juveniles have a light brown wash to their plumage, but this is mostly gone by August. At first, the young have orange feet, which then turn black. A dark bar is visible on juveniles' wrists.

Habitat

The Arctic Tern nests on marshes, tundra lakes, and shorelines in the Arctic, and south on the East Coast to New England. From 1977 to 1995, Arctic Terns nested on gravel islands and parking lots in Everett (Snohomish County). During the non-breeding season, the Arctic Tern is highly pelagic, spending most of its time on the open ocean, far from land.

Behavior

The Arctic Tern forages by flying slowly upward, hovering briefly, and dropping from the air to catch prey below the water's surface. They also steal food from other birds, startling them into dropping their catch by swooping at them. Arctic Terns are seldom seen resting directly on the water, even during their long migration. They may, however, be seen perched on floating logs and other debris.

Diet

Diet varies with season and location, but is primarily fish, crustaceans, and insects.

Nesting

Arctic Terns don't breed until they are 3-4 years old. Both sexes help build a nest on the ground in a colony, sometimes mixed with other species of terns. The nest is out in the open, a shallow depression, often lined with plants and debris. Incubation is by both sexes and lasts about 3 weeks. The parents vigorously defend the nest, dive-bombing intruders. One to three days after hatching, the young leave the nest and hide in nearby cover. Both parents help feed the young until they fledge, usually at 3-4 weeks of age. After that, the young stay with their parents for one or two months more.

Migration Status

True long-distance migrants, some Arctic Terns migrate greater distances than any other birds, traveling from the high Arctic to the Antarctic and back every year. This migration is mostly completed well offshore, but occasionally birds are seen from shore.

Conservation Status

Throughout most of its breeding range, no obvious population trends have been observed, as most of its range is remote and protected from the effects of many human activities. At the southern edge of its breeding range on the Atlantic Coast, steady declines have been observed. The small nesting colony found in Everett (Snohomish County) in 1977 is the southern-most nesting location recorded on the West Coast of North America. The nearest regular breeding colony is 825 miles north, in southeastern Alaska. The Everett terns nested on Jetty Island for a few years, but when the vegetation grew up on the island, the habitat became unsuitable for nesting. The colony then moved to a dirt/gravel parking lot on the mainland in the early 1980s. At this unprotected site, the colony was reduced from 10-12 pairs to 2-3 pairs. This small colony persisted in Everett, where many people struggled to move the colony to a more protected site, because the Navy had plans to develop that site. Attempts to move the colony were not successful, and there has been no known breeding of Arctic Terns in Washington since 1995, though a pair was still present in 2000.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Seldom seen from land south of their breeding grounds (and now that there are probably no longer Arctic Terns breeding in Washington), the best way to see them is from offshore boat trips during migration.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | U | U | R | U | F | F | R | |||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

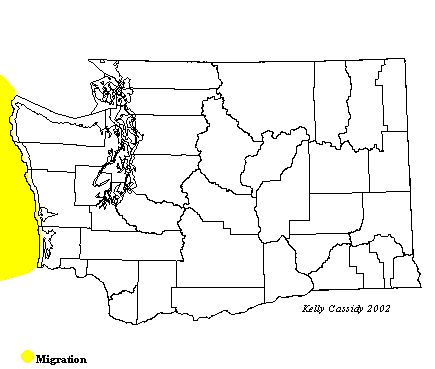

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Laughing GullLarus atricilla

Laughing GullLarus atricilla Franklin's GullLarus pipixcan

Franklin's GullLarus pipixcan Little GullLarus minutus

Little GullLarus minutus Black-headed GullLarus ridibundus

Black-headed GullLarus ridibundus Bonaparte's GullLarus philadelphia

Bonaparte's GullLarus philadelphia Heermann's GullLarus heermanni

Heermann's GullLarus heermanni Black-tailed GullLarus crassirostris

Black-tailed GullLarus crassirostris Short-billed GullLarus canus

Short-billed GullLarus canus Ring-billed GullLarus delawarensis

Ring-billed GullLarus delawarensis California GullLarus californicus

California GullLarus californicus Herring GullLarus argentatus

Herring GullLarus argentatus Thayer's GullLarus thayeri

Thayer's GullLarus thayeri Iceland GullLarus glaucoides

Iceland GullLarus glaucoides Lesser Black-backed GullLarus fuscus

Lesser Black-backed GullLarus fuscus Slaty-backed GullLarus schistisagus

Slaty-backed GullLarus schistisagus Western GullLarus occidentalis

Western GullLarus occidentalis Glaucous-winged GullLarus glaucescens

Glaucous-winged GullLarus glaucescens Glaucous GullLarus hyperboreus

Glaucous GullLarus hyperboreus Great Black-backed GullLarus marinus

Great Black-backed GullLarus marinus Sabine's GullXema sabini

Sabine's GullXema sabini Black-legged KittiwakeRissa tridactyla

Black-legged KittiwakeRissa tridactyla Red-legged KittiwakeRissa brevirostris

Red-legged KittiwakeRissa brevirostris Ross's GullRhodostethia rosea

Ross's GullRhodostethia rosea Ivory GullPagophila eburnea

Ivory GullPagophila eburnea Least TernSternula antillarum

Least TernSternula antillarum Caspian TernHydroprogne caspia

Caspian TernHydroprogne caspia Black TernChlidonias niger

Black TernChlidonias niger Common TernSterna hirundo

Common TernSterna hirundo Arctic TernSterna paradisaea

Arctic TernSterna paradisaea Forster's TernSterna forsteri

Forster's TernSterna forsteri Elegant TernThalasseus elegans

Elegant TernThalasseus elegans