Lapland Longspur

General Description

The Lapland Longspur is a streaked bird, larger than most sparrows. Unlike many sparrows, which normally have unstreaked rumps and tails, the Lapland Longspur has streaks that extend from the back down to the tip of the tail. The male's summer plumage is distinctive--a bold black face, crown, and throat, straw-colored bill, and white brow-line that curves down around in front of his wing. Females and males in non-breeding plumage look similar; they are streaky overall with chestnut on the wings and cheeks edged in black. All plumages have white outer tail feathers. The chestnut nape, visible in all adult plumages, is a good field mark, as well. Unlike most birds with different breeding and non-breeding plumages, longspurs molt only once a year. In the fall, they molt into non-breeding plumage. By spring, the outer tips of the feathers have worn off to reveal the breeding plumage underneath.

Habitat

Lapland Longspurs breed in the high Arctic in a variety of tundra habitats. They prefer wet tundra, thickly vegetated upland areas, sedge-lined stream and pond edges, and sedge marshes. During migration and in winter, they frequent prairies, pastures, and grassy beaches.

Behavior

Lapland Longspurs are known for forming huge flocks, but in Washington, flocks typically number only 10-50 birds, and single birds are often recorded. They sometimes flock with Horned Larks, Snow Buntings, and American Pipits. When flushed, these ground-foragers will fly a long distance away from the disturbance.

Diet

Seeds and arthropods make up the Lapland Longspur's diet. During the summer, arthropods make up about half their diet, although the young longspurs eat a far greater proportion. In winter, seeds are an important diet component. In agricultural areas, they consume waste grain in great quantities as well.

Nesting

Males arrive on the breeding grounds before the females and start to defend and advertise territories. They sing in flight, on the ground, or from a perch (usually a tall weed or wire in their treeless nesting habitat). Once the females arrive, pairing and nesting occurs quickly, as the season is short in these far-northern breeding grounds. The nest, built by the female, is on the ground, usually by a small hummock of sedge, grass, or moss. It is an open cup made from coarse sedge, lined with fine sedge and grass, feathers, or hair. The female incubates the 4 to 6 eggs alone for 10 to 14 days. Both parents help feed the young, which leave the nest at 8 to 10 days of age.

Migration Status

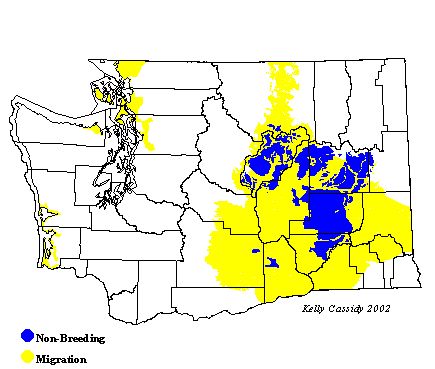

In late fall, Lapland Longspurs migrate in flocks to their wintering grounds across the middle and northern United States, including Washington. They return to the Arctic in the early spring. Peak passage is in November and March.

Conservation Status

While not very common in Washington, range-wide the Lapland Longspur is one of the most abundant breeding birds of the far north. Large yearly fluctuations make it difficult to assess population trends, but much of their breeding range is remote from human disturbance. Potential disturbance in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge could be a threat to the Lapland Longspur population.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Lapland Longspurs are an uncommon winter visitor to Washington. During winter, they can often be found in northern Puget Sound and along the outer coast, and in open prairie of central and southeastern Washington. Mid-September is one of the best times to find migrating Lapland Longspurs, especially in open, grassy areas near Grays Harbor (Grays Harbor County) and Willapa Bay (Pacific County), along the outer coast. They can also be seen moving through the state on their northward migration in April and sometimes into May.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | U | U | U | U | R | R | |||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | |||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | R | R | ||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Green-tailed TowheePipilo chlorurus

Green-tailed TowheePipilo chlorurus Spotted TowheePipilo maculatus

Spotted TowheePipilo maculatus American Tree SparrowSpizella arborea

American Tree SparrowSpizella arborea Chipping SparrowSpizella passerina

Chipping SparrowSpizella passerina Clay-colored SparrowSpizella pallida

Clay-colored SparrowSpizella pallida Brewer's SparrowSpizella breweri

Brewer's SparrowSpizella breweri Vesper SparrowPooecetes gramineus

Vesper SparrowPooecetes gramineus Lark SparrowChondestes grammacus

Lark SparrowChondestes grammacus Black-throated SparrowAmphispiza bilineata

Black-throated SparrowAmphispiza bilineata Sage SparrowAmphispiza belli

Sage SparrowAmphispiza belli Lark BuntingCalamospiza melanocorys

Lark BuntingCalamospiza melanocorys Savannah SparrowPasserculus sandwichensis

Savannah SparrowPasserculus sandwichensis Grasshopper SparrowAmmodramus savannarum

Grasshopper SparrowAmmodramus savannarum Le Conte's SparrowAmmodramus leconteii

Le Conte's SparrowAmmodramus leconteii Nelson's Sharp-tailed SparrowAmmodramus nelsoni

Nelson's Sharp-tailed SparrowAmmodramus nelsoni Fox SparrowPasserella iliaca

Fox SparrowPasserella iliaca Song SparrowMelospiza melodia

Song SparrowMelospiza melodia Lincoln's SparrowMelospiza lincolnii

Lincoln's SparrowMelospiza lincolnii Swamp SparrowMelospiza georgiana

Swamp SparrowMelospiza georgiana White-throated SparrowZonotrichia albicollis

White-throated SparrowZonotrichia albicollis Harris's SparrowZonotrichia querula

Harris's SparrowZonotrichia querula White-crowned SparrowZonotrichia leucophrys

White-crowned SparrowZonotrichia leucophrys Golden-crowned SparrowZonotrichia atricapilla

Golden-crowned SparrowZonotrichia atricapilla Dark-eyed JuncoJunco hyemalis

Dark-eyed JuncoJunco hyemalis Lapland LongspurCalcarius lapponicus

Lapland LongspurCalcarius lapponicus Chestnut-collared LongspurCalcarius ornatus

Chestnut-collared LongspurCalcarius ornatus Rustic BuntingEmberiza rustica

Rustic BuntingEmberiza rustica Snow BuntingPlectrophenax nivalis

Snow BuntingPlectrophenax nivalis McKay's BuntingPlectrophenax hyperboreus

McKay's BuntingPlectrophenax hyperboreus