Semipalmated Sandpiper

General Description

The Semipalmated Sandpiper is a small shorebird in the group known as peeps or stints. The Semipalmated Sandpiper gets its name from the slight webbing at the base of its toes. This can be difficult to see and is not diagnostic, as other sandpipers also have these webbed feet. Its stubby bill and drab plumage help distinguish it from the other peeps, the Least and Western Sandpipers. The adult in breeding plumage is mottled black-and-brown, with little or no rufous coloration. The adult in non-breeding plumage is light gray with a lighter belly. The legs of the adult are black, distinguishing this bird from the yellow-legged Least Sandpiper. In flight, the Semipalmated Sandpiper shows a white stripe down its wings and white on either side of its tail. Juveniles look similar to adults in breeding plumage, and rarely have the rufous coloration seen on juvenile Western and Least Sandpipers. In the late summer when we are most likely to see them, the juveniles have not reached adult plumage, and their legs may be olive-colored.

Habitat

Semipalmated Sandpipers breed in the Arctic tundra, usually near water, across northern North America. During migration and winter, they inhabit beaches, mudflats, shallow estuaries, and inlets. Birds in Washington are usually found in freshwater ponds, even near coastal areas.

Behavior

They are surface feeders, running and stopping frequently, grabbing food from the surface of the sand or mud. They also occasionally probe in the mud. They move faster than Western Sandpipers and feed in shallower water, which may help distinguish the two but is not a surefire distinction.

Diet

During breeding season, Semipalmated Sandpipers eat insects, including flies and larvae, and other invertebrates. The winter and migration diet consists of small crustaceans and aquatic insects, mollusks, and marine worms.

Nesting

Semipalmated Sandpipers first breed at two years. Males arrive on the breeding grounds shortly before the females and begin establishing territories immediately. Monogamous pairs form soon after the females arrive. The male starts several nest scrapes, and the female selects one that they both line with leaves, grass, and moss. The nest is usually located on top of a low mound or small island, under a small shrub or in a sedge tussock. Both parents incubate the four eggs for about 20 days. The young leave the nest soon after they hatch and find their own food immediately. The male broods them quite often during the first four or five days, and for the first eight nights. Females often leave the brood before they fledge, sometimes as soon as the young hatch. Males tend the young until they fledge. The young start to take short flights at 14 to 15 days, and can make sustained flights at 16 to 19 days.

Migration Status

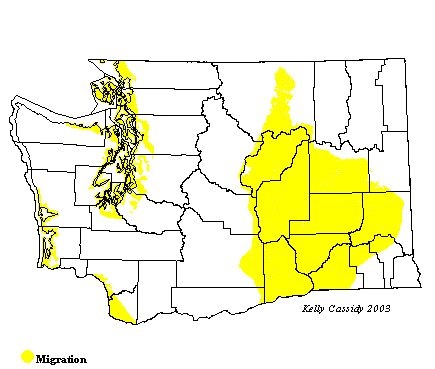

Semipalmated Sandpipers are long-distance migrants. Different breeding populations take different migratory routes, but most winter on the Atlantic coast, south of the United States. The Alaskan breeding population migrates coastally to Vancouver, BC, and then heads inland, moving across the mid-continent in both fall and spring.

Conservation Status

Semipalmated Sandpipers are abundant but vulnerable. The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the population at 3,500,000 birds. They depend heavily on a few key stopover points. Some of these have been protected, but others are vulnerable to development. Habitat destruction remains their biggest threat.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Washington is just outside the normal range of Semipalmated Sandpipers, but slightly off-course migrants are reported regularly during migration. A few birds are usually seen on the coast from late April through May. Adults are seen from late June to mid-August. Juveniles are slightly more common than adults and pass through from late July to mid-September. A few are sometimes seen at freshwater and brackish ponds in the Puget Sound region. Crockett Lake (Island County) is the most reliable place for finding them. They may also appear at the Union Bay Natural Area/Montlake Fill (Seattle, King County). In eastern Washington, they are rare in spring (May), with only a few recorded sightings. In the fall they are more regular, with small numbers of adults passing through in mid-July. There have been a few records at Wenas Lake (Yakima County) in August, but eastern Washington wetlands at the Walla Walla River delta (Walla Walla County), Othello (Adams County), and Reardan (Lincoln County) are more likely spots.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | |||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | U | U | R | ||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | R | R | ||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | R | U | R | |||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius